Property Ownership Calculator

How Your Ownership Percentage Affects Your Rights

This calculator shows how different ownership structures work when you share property in New Zealand. Enter your ownership percentages to see what happens if one owner dies, sells, or wants to exit the arrangement.

When you buy a home with someone else, you might hear the terms joint owner and co-owner used interchangeably. But they’re not the same. In New Zealand, especially in places like Auckland where housing costs push more people into shared ownership, understanding this difference can save you from legal headaches, financial surprises, or even losing your home.

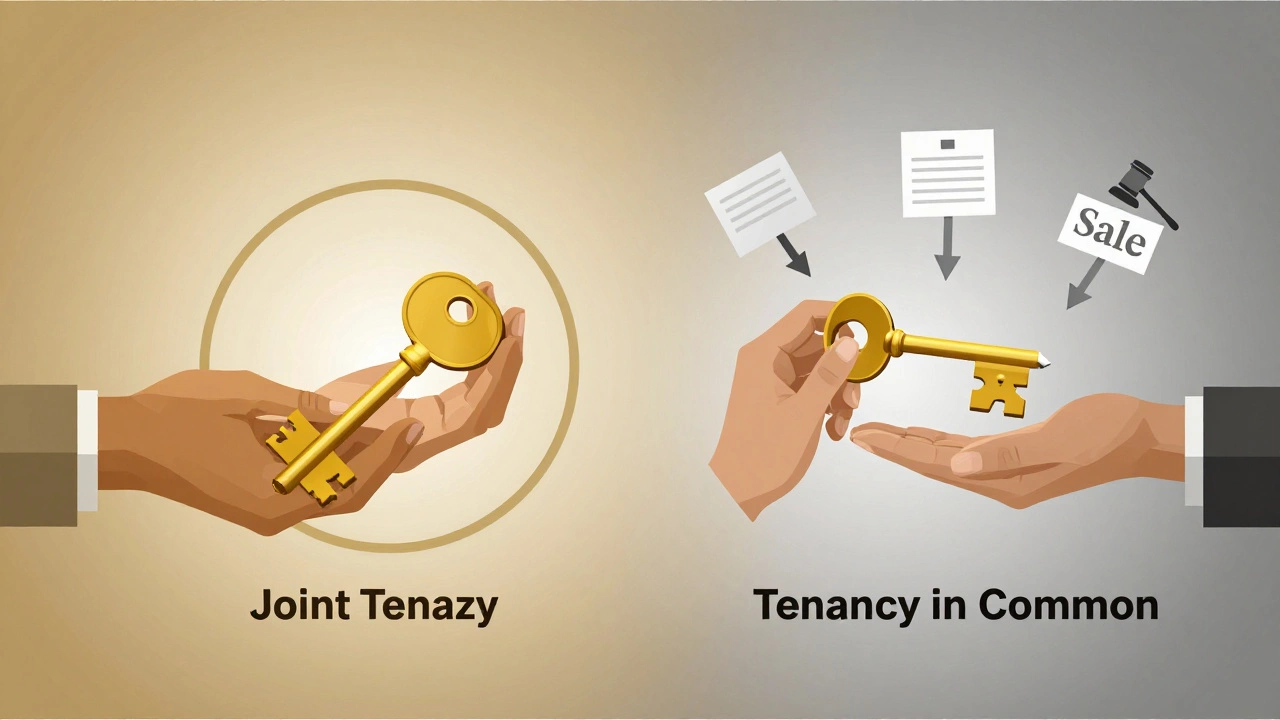

Joint Owner Means You Own It Together - No Matter What

A joint owner holds property under a legal arrangement called joint tenancy. This isn’t just about sharing space or splitting bills. It’s about ownership that’s inseparable. If you and your partner are joint owners, you each own 100% of the property - not 50%. That sounds strange, but here’s how it works: when one joint owner dies, their share doesn’t go to their family, their will, or their creditors. It automatically passes to the surviving joint owner. No probate. No delays. No disputes.

This is why many married couples or long-term partners choose joint tenancy. If you bought a home with your spouse and they passed away, you’d own the whole thing without needing to go to court. The title changes automatically. It’s simple, fast, and designed for people who want their partner to inherit everything without paperwork.

But there’s a catch. You can’t sell your half, give it away, or leave it to someone else in your will. You don’t have a separate share to transfer. If you try to sell your interest, the joint tenancy breaks and turns into a tenancy in common - which brings us to co-owners.

Co-Owner Means You Own a Defined Share - And Can Do What You Want With It

A co-owner is usually a tenant in common. This is the most common setup when friends, siblings, or unrelated people buy property together. Each person owns a specific percentage - say, 60% and 40%, or 50/50. That share is theirs to do with as they please. They can sell it, gift it, mortgage it, or leave it to their child in their will.

Let’s say you and your best friend bought a two-bedroom apartment in Ponsonby. You put in 70% of the deposit, they put in 30%. You register as tenants in common with those exact percentages. If your friend moves overseas and needs cash, they can sell their 30% to someone else - even a stranger - without your permission. You can’t stop them. And if they die, their 30% goes to their estate, not to you.

This flexibility is great for investment groups or people who don’t trust each other enough to assume the other will die first. But it also means more complexity. If you want to sell the whole property later, you need everyone’s agreement. If one person refuses, you might need to go to court for a forced sale - a messy, expensive process.

How the Law Treats Them Differently in New Zealand

In New Zealand, both joint tenancy and tenancy in common are recognized under the Property Law Act 2007. But the rules are strict. For joint tenancy, the four unities must be present: unity of possession (you both have equal access), unity of interest (same type of ownership), unity of title (same deed), and unity of time (bought at the same time). If any one of these breaks - say, one person inherits their share instead of buying it - the joint tenancy is destroyed.

With tenancy in common, none of those unities matter. You can buy in at different times, pay different amounts, and hold different shares. The law doesn’t care. What matters is what’s written on the title. That’s why getting the right title type from the start is critical.

Many people don’t realize they’ve accidentally become tenants in common. For example, if you bought a home with your sibling and used separate bank accounts to pay the mortgage, the lawyer might have set it up as tenancy in common by default. If you thought you’d automatically inherit their share, you’re in for a shock.

What Happens When Things Go Wrong?

Joint ownership works beautifully until someone wants out. Let’s say you’re a joint owner and your partner suddenly wants to sell. You don’t. You can’t force them to stay, but you also can’t sell without them. The only way out is mutual agreement, or a court order under the Property (Relationships) Act 1976 - which can take months and cost tens of thousands.

With co-ownership, the problem is different. If you own 60% and your co-owner owns 40%, and they stop paying their share of rates or maintenance, you can’t just take over their portion. You can pay it for them, but you can’t claim it back unless you have a written agreement. Many people don’t have one. That’s why disputes over repairs, rent, or sale timing are so common.

That’s why a co-ownership agreement is essential - even if you’re best friends. It should say who pays what, how decisions are made, what happens if someone dies, gets sick, or wants to sell. Without it, you’re relying on goodwill. And goodwill doesn’t pay the mortgage when someone walks away.

Which One Should You Choose?

Here’s a simple rule:

- Choose joint ownership if you’re in a committed relationship - married, civil union, or long-term partner - and you want the surviving person to inherit everything automatically.

- Choose co-ownership (tenancy in common) if you’re buying with someone you’re not romantically involved with - a friend, family member, or investor - and you want control over your own share.

There’s no legal advantage to one over the other. It’s about your relationship and your goals.

Some people think joint ownership is safer because it avoids probate. But if you’re not married and you die, your partner doesn’t automatically get your share - even if you’re joint owners. The law doesn’t recognize de facto relationships for automatic inheritance unless you’re married or in a civil union. So if you’re an unmarried couple, joint tenancy won’t protect your partner unless you’ve made a will or have a relationship property agreement.

What’s on the Title Sheet Matters More Than What You Say

At the end of the day, it’s not what you think you agreed to. It’s what’s written on the land title. If your lawyer says, “We’ll put it as joint owners,” and you don’t check the document, you might end up with tenancy in common because the form they used defaults to that.

Always ask to see the title before signing. Look for the words:

- “as joint tenants” - that’s joint ownership

- “as tenants in common” - that’s co-ownership

If it says nothing, it’s assumed to be tenancy in common. That’s the default under New Zealand law.

One real case from Auckland: a woman bought a house with her brother. They didn’t sign anything. She paid 80% of the mortgage. He moved out after two years and stopped paying. When she tried to sell, she found out they were tenants in common - and he owned 50%. He refused to sell. She spent $18,000 in legal fees just to get a court order to force the sale. She lost $12,000 in equity.

Don’t Skip the Paperwork

Shared ownership isn’t just about splitting rent or chores. It’s a legal partnership. You need:

- A clear title type - joint tenancy or tenancy in common

- A written co-ownership agreement - even if it’s just a one-page document

- Updated wills - especially if you’re tenants in common

- Life insurance - to cover your share if you die

Many people think, “We’re friends. We don’t need paperwork.” But friendships change. Jobs move. Relationships end. The law doesn’t care about your feelings. It cares about what’s on paper.

If you’re thinking of buying with someone, talk to a lawyer before you sign anything. Don’t rely on your real estate agent. They’re not legal advisors. A $300 consultation now can save you $30,000 later.

Corbin Fairweather

I am an expert in real estate focusing on property sales and rentals. I enjoy writing about the latest trends in the real estate market and sharing insights on how to make successful property investments. My passion lies in helping clients find their dream homes and navigating the complexities of real estate transactions. In my free time, I enjoy hiking and capturing the beauty of landscapes through photography.

view all postsWrite a comment